Vocation Stories

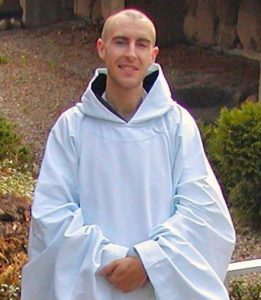

Father IsaacGenessee Abbey

“Seeking the work of the heart.”

Father Isaac won the 2007 America Magazine Foley Poetry Contest with “Lost and Found” by John Slater. Slater is the pen name of Father Isaac, a monk of Genesee Abbey in upstate New York. Born in Toronto, Ontario in 1974, Father Isaac studied classics at Trent University before entering the monastery in December 1999. The following is an interview with Isaac by America magazine:

How long have you been writing poetry?

Sporadically-lifelong; daily, intensively-for the last 6 or 7 years.

Why did you start writing?

That’s something I continue to discover each time I’m given a poem to make. Stanley Kunitz spoke of one’s art as “the gift you have made to the world in acknowledgment of the gift you have been given, which is the life itself. And I think the world tends to forget that this is the ultimate significance of the body of work each artist produces. It is not an expression of the desire for praise and recognition, or prizes, but the deepest manifestation of your gratitude for the gift of life.”

“Lost and Found,” I suspect, grew from and, I hope, expresses, some ray of gratefulness for the encounter it describes.

Why did you choose to join the Cistercians?

That’s also something I continue to discover. The silence, solitude and concentration, the simplicity of the life attracted me. Merton’s “Seven Storey Mountain” and “New Seeds of Contemplation” meant a great deal to me; that someone with his passion for writing could make a go of it as a monk was encouraging as well. The first Cistercians called the monastery a “school of love”; there’s nothing more important to learn, and nothing I need more help learning. Monastic life can serve as a way to remain true and faithful to the experience of God’s mercy and forgiveness that one has enjoyed-and to our heart’s own deepest desire.

Ultimately, of course, it was God who chose me for the life not the other way around.

Do you see any connections between your vocation as a monk and your vocation as a poet?

There are many connections: a degree of quiet and solitude, reading, leisure, “the work of the heart,” a certain marginality…

There are many connections: a degree of quiet and solitude, reading, leisure, “the work of the heart,” a certain marginality…

Cloistered monastic life is something like living in a sonnet. There is a definite skeleton, a strict set of norms and limits given. For the poet, the rhyme-scheme and so on can challenge and stretch his imagination in fresh and surprising ways; they force him to question what is essential to the work and to prune away the superfluous. The rules exist to secure and support a certain inner liberty-at the same time the very freedom unleashed, intensified by confinement in such tight quarters (monastic life is also like bonsai) tests and pulls against the edges. Where the mind of the poem wants to go is ultimately more important in discovering its true form than adherence to external rules… just as charity often demands of monks that they bend the rules, miss an office to care for a sick brother or something.

What is your average day like at Genesee?

This question prompts me to note that grace is not always disruptive; there’s a grace of everydayness too, what one monastic writer calls “creative monotony.” We wake at 2 a.m. for Vigils, the first of seven times of communal prayer; after that there is a 2 to 3 hour stretch of silent prayer and reading. The rest of the day is a balance of work and prayer with intervals to read, rest and shift gears. The Mass is the center of our day, what everything flows from and converges on…